The Wheelwright Museum’s collections number over 12,000 items, including jewelry, metalwork, pottery, basketry, folk art, works on paper, and textiles of the Navajo, Rio Grande Pueblo, and other Native peoples of New Mexico.

The Wheelwright Museum archival holding number is around 456 linear feet, including the papers of scholars and artists, including John Adair, Kate Peck Kent, Laura Adams Armer, Caroline B. Olin, Byron Harvey, Washington Mathews, Mary Cabot Wheelwright, Frances Newcomb, and many others (see below for archival finding aids).

Most of our stored collections and archives are publicly accessible; however, this is by appointment only. We advise that requests should be sent 4 weeks in advance. Certain collections are restricted and require advance permission through an application to Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department.

Inquiries should be made first by email, detailing the purpose of your visit and the resources you wish to access. We will make our best effort to contact you as soon as possible.

For collection inquiries, contact our Collections Department at collections@wheelwright.org or 505-982-4636 ext. 115. For archives-based inquiries, contact our Archivist at nbyers@wheelwright.org

IMLS and Mellon Foundations Grant Update

The Wheelwright Museum is pleased to report that we have successfully completed three grant-funded projects to improve the public accessibility of museum collections and archives.

In 2020, a generous $50,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) allowed us to hire student intern Nataani Hanley Moraga, purchase new compactor storage, move the museum archives, create a new workstation for an archivist and researchers, update our computer database, and enhance our social media posts.

We also received a significant $36,636 grant from IMLS in 2021. This ambitious project allowed the museum to migrate its aging database from Filemaker Pro to Rediscovery’s Proficio collections management system, so that our collections can be researched from a link on the museum’s web site (called Proficio on the Web). This grant also brought in student interns Danielle Hena, Charles John, and Nataani Hanley Moraga to assist with the project, and funded needed equipment and supplies including a freezer for pest prevention, insect traps, UV-filtering window film, laptops for collections management, collections photography equipment, and data loggers to monitor temperature and humidity in museum spaces. Funds from IMLS also allowed us to begin adding the archives to the new Proficio database.

Most recently we completed a $500,000 grant project through the generosity of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This project supported staff capacity and allows us to continue the process of making our collections available on the Web by providing additional computer hardware, improving the Museum’s web site, moving the museum’s archival records to a new location, collections photography and cataloging, digitizing materials from the John Adair Archives, posting finding aids to the new web site, and launching a pilot project to post on-line images of the collection and write collections summaries to increase access to the collection with the assistance of student interns Kateri Smith and Mérida Mehaffery. The impact that the Mellon grant has had on the museum is evident in our exhibitions and programs, and in a dedicated display on the lower level which tells the history of the museum, its exhibitions and its work with generations of Native American artists.

We are grateful to IMLS and the Mellon Foundation for their support of these important projects, which not only bring visibility and accessibility to the Wheelwright Museum and its collections and exhibitions, but also help facilitate the career paths of Native American students, and other emerging professionals wanting to develop a career in museums.

Archives

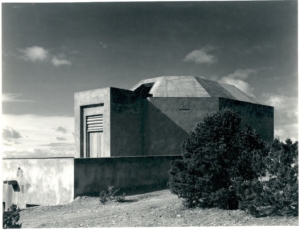

Photograph to left taken by Ernest Knee.

This black and white print of the House of Navajo Religion, later the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art and later the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, is but one such item in the Museum’s Archival holdings. This representation of the museum at opening, highlighting its architecture inspired by a traditional Diné Hooghan, exemplifies the dual roles the archive hopes to fill: serving to preserve the history of the institution and acting as a repository for research on Native American arts and culture. Continuing with this duality, the museum’s archives are split into two major groups of collections, the Administrative Records and the Manuscript Collections.

The Administrative Records (AR) group contains 28 collections and spans 168 linear feet. The collections within the group span the entire history of the museum from its founding documents in 1937 to the present. The AR collections contain documentation, photographs, correspondence, etc. that pertains to all the major activities of the museum and its day-to-day operations. Some notable AR collections are AR 3 Board of Trustees, AR 6 Director’s Correspondence, and AR 13 Exhibits. AR 3 Board of Trustees contains minutes from every Board meeting the museum has held since its inception in 1938. It also has subseries containing numerous committees within the board and their activities and reports. AR 6 Director’s Correspondence contains a large selection of the correspondence of our nine past and present directors. AR 13 Exhibits chronicles the temporary exhibition program, and includes planning documents, photographs, correspondence, label text, draft interviews and publications linked to the exhibitions of contemporary and historic art the museum has created since its focus shifted to contemporary Native American art in the 1970s.

The Manuscript Collections (MS) group contains 59 collections and spans 288 linear feet. The MS series is focused on the study and appreciation of Native American arts and culture. Important MS collections are MS 1 Mary Cabot Wheelwright Papers, MS 5 Washington Matthews Collection, MS 13 Frances Newcomb Research Notes and Manuscripts. MS 1 Mary Cabot Wheelwright Papers are Mary Cabot Wheelwright’s collection of firsthand accounts of and research notes on Diné ceremonials, which were her primary interest. collection is restricted. It also contains several photograph albums of her world travels. MS 5 Washington Matthews Papers contain the notebooks and publication drafts of Washington Matthews, a very early scholar in the field of Diné religion. The collection also contains a microfilm copy of itself. MS 13 Frances Newcomb Research Notes and Manuscripts contain the research notes and manuscripts of Frances Newcomb—a trader who, through her residence and work, developed an intimacy with Diné culture and was the connecting thread between our two founders, Hastiin Klah (1867-1937) and Mary Cabot Wheelwright (1878-1958). Access to these collections requires permission to be granted by Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department (NNHHPD), Window Rock, prior to booking an appointment to view the manuscripts.

MS 18 John Adair Collection is one of our largest archival collections and contains the research and other documents of anthropologist John Adair during his work at Many Farms and Pine Springs in Navajo Nation. They pertain especially to his publication in 1944 Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, a reference text on jewelry making in the Southwest substantiated by extensive quantitative and qualitative research. This collection is the most important twentieth-century archive on Navajo and Pueblo silver and includes fieldnotes, more than 1,000 photographs, movie film, videotapes, sound recordings, and other material.

A separate finding aid is accessible for MS 18 and the archives have been digitized. In addition the manuscript collection includes archives linked to the works of mid-twentieth century Diné silversmith Johnny Pablo (MS 61), the papers of David L. Neumann (MS 60), who published on the technology, trade, and marketing of Navajo and Zuni jewelry during the mid-twentieth century, as well as the research archives of Alison Bird Romero (MS 64) and Dexter Cirillo (MS 74) who have published on jewelry. A full list of the Administrative Records and Manuscript collections can be found here.

Access to the archives is by appointment only: nbyers@wheelwright.org.

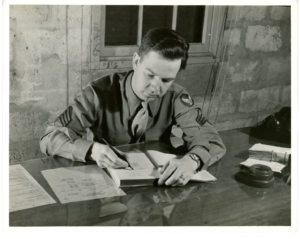

Cameras used by John Adair and notes on the making of earrings in Zuni Pueblo in the 1930s. Photograph taken by Addison Doty.

“Me in Army, Santa Monica, 1944” John Adair signing Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. The Adair archives includes many photographs, Adair’s papers indicates that he had hoped his book would be published as a large-format art book with color illustrations. That he was unable to fulfill this goal was largely due to the impact of World War II.

Archival Finding Aids

Our Archive contains numerous collections pertaining to the running and history of the Museum and scholars in the fields of Native American Arts and Culture. In order to improve access for researchers and scholars we have created DACS compliant finding aids for many of our collections. This is an ongoing project and the finding aids listed below are not the extent of our archival holdings. The links below will download the listed finding aid.

Administrative Records

- AR001 Articles of Incorporation and Founding Documents

- AR002 Accreditation

- AR003 Board of Trsutees

- AR004 Wheelwright Museum Foundation

- AR005 Financial

- AR006 Director’s Correspondence

- AR007 Weavings, Sandpaintings, and Chants

- AR008 Lawsuits and Legal Matters

- AR009 Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Arts General Files

- AR010 Assistant Director

- AR011 Assistant to Director

- AR012 Publications

- AR013 Exhibits

- AR014 Buildings and Grounds

- AR015 Conservation

- AR016 Curatorial

- AR017 Grants

- AR018 NAGPRA

- AR019 Events

- AR020 Education

- AR021 Friends of the Wheelwright

- AR022 Case Trading Post

- AR024 Photographs

- AR025 Mary Cabot Wheelwright Research

- AR026 Development

- AR028 Operations

Audio Visual Collections

Manuscript Collections

- MS001 Mary Cabot Wheelwright Papers

- MS002 Father Berard Haile Chant Collection

- MS003 Dr. Harry Hoijer Collection

- MS004 Leland C. Wyman Manuscript Collection

- MS005 Washington Matthews Papers

- MS006 Byron Harvey III Collection

- MS007 John Frederick Huckel Collection

- MS009 Kate Peck Kent Papers

- MS011 A.H. Whiteford Papers

Native American Jewelry

The Wheelwright Museum’s jewelry collection comprises approximately fifty percent of the permanent collection and over seven hundred dazzling works are on semi-permanent display in the Jim and Lauris Phillips Center for the Study of Southwestern Jewelry.

Jewelry making in the Southwest is major artform, and in the public imagination encoded in the combination of silver and turquoise. As an artistic domain it is highly dynamic and constantly influenced by, and responsive to, the economic and cultural history of the region, including government policy, collecting markets, the curio trade, and the availability of raw materials like turquoise and silver. Diné silversmithing first emerged in the 1850s dating from after the internment of Diné people at Bosque Redondo in southern New Mexico, influenced by local blacksmithing. Early silversmithing build upon pre-existing indigenous jewelry traditions, notably those of Pueblo and Diné communities who have long produced, worn and traded jewelry made with coral, shell, and stone. Charting the early history of silverwork, we see the emergence of the iconic styles of the Southwest from the 1870s – the squash blossom necklaces and concho belts – reflecting the importance of settlers, artists and tourists coming with the railroad as consumers and patrons of the artform. Works made from both precious and non-precious materials reflect changes in the availability of different materials throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Aesthetic and design sensibilities are never fixed, with distinct Pueblo and Diné visual traditions emerging and influencing one another in parallel and intersecting creative moments. Intergenerational knowledge of materials and techniques is maintained in families and communities, forming links between artists whose work is featured in the Wheelwright Museum’s collection.

The seeds of the Wheelwright Museum’s collection were established by the 1960s with jewelry a significant proportion of the existing collection. In 1966, when anthropologist Bertha Dutton became director of the Wheelwright, she engaged long-time associate Byron Harvey III to develop a jewelry collection. In 1968 Harvey purchased the collection of trader Steve Hambaugh, which consisted of 84 pieces, primarily bracelets and rings, gathered “in the thirties and forties from quite a roster of western reservation posts,” and donated these to the Wheelwright. Between 1968 and 1975, Harvey donated more than 265 examples of Navajo and Pueblo jewelry.In the 1990s, jewelry became a focus aided by two important collections. A key collection was one acquired by philanthropist and botanist Leonora Scott Curtin (1879-1972) who starting in the mid-1920s assembled an unparalleled collection of Zuni stone carvings by the first generation of Zuni artists who carved for a commercial market, many recognized as master lapidarists and jewelers, including Leekya Deyuse (1889-1966), Leo Poblano (1905-1959), and Teddy Weahkee (ca.1895-1965). When in 1995, the Wheelwright Museum acquired the papers of anthropologist John Adair (1913-1997) our commitment to jewelry came into sharper focus. Adair worked in the community of Pine Springs, Arizona. He had sustained relationships with many of the silversmiths and lapidary artists he worked with, an approach that is embodied today by the Wheelwright Museum’s partnerships with contemporary Native jewelers.

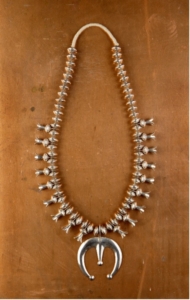

The impressive size and scope of the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection allows artistic movements, historical moments, and individual artists’ voices to be mapped over time. One of the strengths of the Wheelwright Museum’s collection is that many of the earliest jewelry works are documented or attributed to known makers, such as the shell and stone necklace worn by Hastiin Klah, and the silver squash blossom necklace made formerly owned by Navajo Tribal Chairman Chee Dodge, and made by the master silversmith Slender Maker of Silver (Béésh-łigaii il’ini Alt’so’sigi, d. 1916). Collections strengths include ‘thunderbird’ or ‘depression era’ jewelry from Kewa (Santo Domingo) Pueblo; an important collection of Zuni fetish carving by pioneers of the artform; the Carl Lewis Druckman collection of Navajo and Pueblo Spoons and a collection of New Mexican filigree work donated by George T. Anderman and Bob Gallegos. Substantial collections exist of work by artists such as Charles Loloma (1921-1991, Hopi) and Preston Monongye (1927-1987, Mission Hopi), both known for their imaginative style and modern designs which challenged conventional perceptions of “Indian art” and “Indian jewelry”. There is a strong representation of works by mid-twentieth century artists such as Kenneth Begay (1912-1977, Navajo), Lewis Lomay (1913-1996, Hopi), Joe Quintana (1915-1991, Cochiti Pueblo), and Morris Robinson (1900-1987, Hopi) with more potential for growth as regards Hopi jewelers such as Victor Coochwytewa (1922-2011). This draws attention to the ways in which these artists responded to this key moment in design history, one characterized by the prevalence of modernism and the post-war craft resurgence. It allows researchers to trace the careers of important figures showing the significant influence they had on one another, and highlights the skills, techniques, aesthetic tastes, and creativity of different generations of artists.

The collection includes jewelry made by artists for themselves and family members, or commissioned for the museum.

The museum has a commitment to organizing major solo shows, including in 2005 the retrospective Loloma: Beauty is his Name. This highlighted Loloma’s significance, and today the Wheelwright Museum has the capacity to chronicle all periods of this gregarious and ingenious jewelry maker’s life through an outstanding collection of his pieces. Our collection features important numbers of work by major contemporary living artists including Gail Bird (Santo Domingo Pueblo/Laguna Pueblo), Richard Chavez (San Felipe), Larry Golsh (Pala Mission/Cherokee), Yazzie Johnson (Navajo), James Little (Navajo), Norbert Peshlakai (Navajo), McKee Platero (Navajo), Verma Nequatewa (Sonwai, Hopi), Angie Reano Owen (Santo Domingo), Mike Bird-Romero (Ohkay Owingeh), Sylvia Begay Radcliffe (Navajo), Kay Begay Rogers (Navajo), Perry Shorty (Navajo), Denise Wallace (Chugach Sugpiaq), Liz Wallace (Navajo/Maidu/Washo).

The Wheelwright Museum to represent the story of jewelry in the Southwest as an ever-changing artistic expression linked to individual and communal experiences. Jewelry can hold spiritual meaning, store wealth, convey political ideas, and record moments in history. As a vital indigenous aesthetic expression, it reflects the cultural, economic, and material history of the Southwest.

Access is by appointment only, and all inquiries should be made emailing: collections@wheelwright.org.

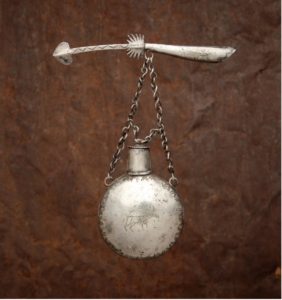

Jake the Silversmith (Naltsòs Nigehani, d. 1895, Diné)

Canteen and powder measure ca. 1880

Purchased with funds donated in memory of Beatrice M. Loennecke, and gifts from anonymous donor and Collectors’ Circle

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Slender Maker of Silver (Béésh-łigaii il’ini Alt’so’sigi, d. 1916, Diné)

Squash blossom necklace, ca. 1885-1890

Provenance: Commissioned by Henry Chee Dodge. Sold Sotheby’s in 1987

Purchased with funds donated by Thaw Charitable Trust and Collectors’ Circle

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Maker not yet known, Diné

Bridle, ca. 1910

Gift of Stewart Otis

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Maker not yet known

New Mexican gold filigree tie pin and pin with turquoise, ca. early twentieth century

Gift of George Taylor Anderman

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Theodore Kucate (Zuni)

Dragonfly of Ojo rock with turquoise and pitch, ca, 1935

Provenance: Leonora Scott Curtin

Gift of Leonora C. Paloheimo

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Ambrose Roanhorse (1904-1982, Diné)

Squash blossom necklace, ca. 1955

Provenance: Winfield Scott Wellington

Gift of Susan Brown McGreevy

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Julian Lovato (1915-2018, Santo Domingo Pueblo)

Silver and coral squash blossom with hands, ca. 1970s-80s

Provenance: private collection in Texas

Purchase supported by the Daniel E. Prall Fund

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Johnny Rosetta (Santo Domingo (Kewa) Pueblo)

Fossil Ivory, turquoise, coral, lapis and shell necklace, 1977

Anonymous donor

Photograph taken by Addison Doty

Charles Loloma (1921-1991, Hopi),

Tufa cast gold bracelet with coral, turquoise, and lapis lazuli, 1985.

Gift of John and Ann Stewman.

Photograph taken by Addison Doty.

Perry Shorty (Navajo)

Silver concha belt, 2000

Given by anonymous donor.

Photograph taken by Addison Doty.

Liz Wallace (Navajo/Washoe/Maidu)

Spoons fashioned after Northern California mush spoons, 2003

Gift of the artist and of Jim and Jeanne Manning

Photograph by Addison Doty

Jim and Lauris Phillips Collection (Native American Jewelry)

In 2013, the estate of Jim Phillips (1926–2012) and Lauris Phillips (1928–2013) of San Marino, California, donated one of the most extensive jewelry collections to the Wheelwright Museum. Comprising more than 1,800 examples of Navajo and Pueblo silverwork, lapidary work, and blacksmithing, its many masterworks illustrate the evolution of technology and design. Some 144 works from this collection are on view in the permanent display in the Jim and Lauris Center for Southwestern Jewelry.

Lauris Phillips was the jewelry collector who became interested in Navajo and Pueblo jewelry in the 1960s, having inherited her mother’s jewelry. She favored women’s jewelry and ornaments, especially buttons, collar tabs, and pins although she equally avidly collected bracelets, necklaces, and belts, worn by women and men. As an accomplished equestrian Lauris Phillips also loved superbly designed Diné bridles, donating sixteen to the museum’s collection. In the 1970s, Lauris’s and Jim’s growing interest in Native American arts led to their founding of Fairmont Trading Co. becoming active dealers in the jewelry field during the high point of the 1970s. While jewelry was a conspicuous focus, they also specialized in southwestern and California basketry, and in Navajo textiles. Over time, they amassed one of the finest collections of jewelry made between about 1870 and 1940, plus a large collection of the work of Navajo master Fred Peshlakai.

Lauris Phillips was an avid researcher and documented her sources of early jewelry, creating a timeline for early silver jewelry that she shared with curators and researchers. One source she documented was Cozy McSparron (a trader at Chinle, Arizona, of the 1920s), the source of an early Navajo belt on display in the gallery. Other pieces in the collection were sourced to the Traphagen School in New York, whose focus was fashion, which was open for nearly 60 years (1923 – 1991) teaching more than 20,000 students.

A key source of reference for Phillips was John Adair’s 1944 book, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. She held Adair in high esteem and admitted two regrets: not meeting John Adair and not meeting the Los Angeles-based Diné silversmith Fred Peshlakai. Lauris Phillips’s attention to finding and identifying his work has ensured over time that he is recognized—along with his brother Frank Peshlakai—as one of the leading silversmiths of his generation.

Fred Peshlakai was born in 1896, one of at least three children born to the second wife of Slender Maker of Silver, a first-generation master smith. In 1930 or 1931, Peshlakai moved to Gallup, New Mexico, where he learned commercial metal casting techniques and was soon hired as the first instructor of silversmithing at the Charles H. Burke School in Fort Wingate, New Mexico. In 1933 he demonstrated his craft at the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition. Fred Peshlakai left the Burke school in 1935, working briefly for Reese Vaughn of Vaughn’s Indian Store in Phoenix, Arizona, prior to opening a shop in Los Angeles in 1938. Peshlakai rarely worked for others and insisted upon managing his own career for most of his life. He was one of a growing number of Native American silversmiths who, through their own initiative, joined the ranks of modern studio jewelers.

Hosteen Goodluck (Navajo, active at Zuni Pueblo)

Squash-blossom necklace, 1927

Handwrought and tufa-cast silver

Provenance: C. G. Wallace

Gift of Jim and Lauris Phillips

Zuni Pueblo

Bracelets, ca. 1925 (left) and 1935 (right)

Left: handwrought silver, turquoise

Right: Attributed to Juan de Dios

Commercial sheet silver turquoise

Provenance: Traphagen School Museum, New York

Gift of Jim and Lauris Phillips

Fred Peshlakai

Bracelets, ca. 1940–1955

Silver, Blue Gem turquoise

Hallmarked “F.P.” with long arrow

Fred Peshlakai

Bracelets, ca. 1960

Silver, Lone Mountain turquoise. Peshlakai frequently used large cabochons of Lone Mountain turquoise.

Hallmarked “FP” with short arrow

Fred Peshlakai

Bowl, ca. 1960

Silver

Hallmarked “FP” with arrow pointing right. The size of the work and unique hallmarks suggest that this piece was made for public display or an exposition of some kind. This

is also stamped “trade mark.”

Charlie Houck (Navajo)

Tufa-cast bracelet, ca. 1935

Silver, turquoise

Gift of Jim and Lauris Phillips

Sidney and Ruth Schultz Collection (Native American jewelry)

In 2022, the Wheelwright Museum received an important jewelry collection from the estate of Sidney (1921-2022) and Ruth (1923-2019) Schultz. Living on the East Coast and friends since their early teens, the Schultzs moved from Louisiana to Albuquerque in the 1950s to enable Sid to pursue his medical career. This was a life-changing choice. Ruth initially a ‘reluctant transplant’ soon found comfort and pleasure in looking at, and buying, Native American jewelry.

As a young couple, the Schultzs had limited means and bought selectively in popular shops of the period: shops like White Hogan, Scottsdale, or Prices’ All Indian Shop in Albuquerque. Sid Schultz enjoyed and collected the work of Navajo jewelry Johnny Pablo. Ruth Schultz’s taste in jewelry was aesthetically informed by Kenneth Begay (1912-1977) whose work she looked for and with whom she became friends. Ruth collected many pieces over time, starting while Begay was at White Hogan (1946-1964), and continuing when he worked for Navajo Arts and Crafts and taught at Diné Community College (1968-1973). The Schultzs collection includes stunning pieces made in the 1970s, which his daughter Kay Begay Rogers believes to be more connected to, and expressive of, his great skill and independent artistic vision.

In time with an adventurous spirit, increasing means, and a new dedication to the place where they settled, they became more invested in the Native American art field, evident in the gradual filling up of their home. Sid and Ruth were regularly seen at the Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial, Navajo Nation fairs, the Eight Northern Pueblo shows and Indian Market in Santa Fe, an event which Ruth supported in multiple of ways up until to her death.

As the Schultzs’ collection grew, they started to buy retrospectively, influenced by gallerists and traders who carried historic work. During this period, they bought pieces by Begay and other significant jewelers such as Leo Poblano (1905-1959, Zuni Pueblo) and established artists such as Virgil Benn (Zuni Pueblo), Shirley Benn (Hopi/Tewa) and Norbert Peshalakai (Diné). Ruth enjoyed purchasing from women artists and her collections include numerous representations of women. Eschewing a definition of themselves as collectors, they built strong and lasting relationships with artists working across varied media. As part of the gift, the Wheelwright Museum acquired documentation linked to the artworks which establishes provenance and gives valuable insight into the relationships between the Schultzs and the artists and galleries they purchased from.

Access is by appointment only, and all inquiries should be made emailing: collections@wheelwright.org.

Kenneth Begay, 1913 -1977 (Navajo)

Necklace of silver and Persian turquoise with large pendant, 1977

Provenance: Foutz family and Jim Price of Prices’ All Indian Shop, Albuquerque

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Kenneth Begay, 1913-1977 (Navajo)

Stamped spiral silver bracelet set with Morenci turquoise, ca. 1970s

Provenance: Kenneth Begay through Foutz family.

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Kenneth Begay, 1913-1977 (Navajo)

Cuff bracelet, with coral and Lone Mountain turquoise, 1976

Provenance: One of two commissioned from Begay in 1976, resized later by Harvey Begay.

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Cippy Crazyhorse (Cochiti Pueblo)

Silver bracelet with eight rows of ‘shaped eyes’, 1993

Provenance: Purchased from artist

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Raymond Yazzie (Navajo)

Silver bracelet inlaid with Kingman and Orville Jack turquoise, lapis lazuli, sugilite and Australian opal, 2012

Provenance: Commissioned by the Schultzs from Yazzie in 2011

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Jennifer Curtis (Navajo)

Silver stamped bracelet with 14kt gold appliqué diamonds, 2008

Provenance: Purchased from artist at Santa Fe Winter Market

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Overlay inlay silver bracelet with prominent image of a bear, early 1970s

Preston Monongye, (1927-1987, Mission/Mexican) and Lee Yazzie (Navajo)

Provenance: California collection, purchased in 2009

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Darryl Dean Begay (Navajo)

In Beauty it has Become, 2007

Provenance: Purchased at Indian Market

Estate of Ruth and Sidney Schultz

Photograph taken by Ben Calabazza

Paintings & Works on Paper

Indian Landscape by Fritz Scholder (1937-2005, Luiseño) and Witch Seed I, #1147 by Emmi Whitehorse (Diné), both part of the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection, show the dynamic range of contemporary 2-D art in the collection. Beginning in the 1970s, the Wheelwright Museum shifted focus towards contemporary Native art, reflected by the acquisition and display of works on paper. The World in Chaos, made by Michael Kabotie (1942–2009, Hopi) in 1964, was the first work in the permanent collection to be consciously recorded as contemporary Native art. Since then, the Wheelwright Museum has aimed to advocate for and support the work of emerging and established Native artists, building a reputation for well researched solo shows and thematic exhibitions. The museum’s vision statement of honoring Native voices through art is embodied by the diverse exhibition programming over the last century.

Works on paper are an important subset of the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection, including lithographs, paintings, prints, collages, and drawings. The extensive collection features works by renowned artists such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b. 1940, citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation), Marwin Begaye (Diné), Harry Fonseca (1946-2006, Nisenan Maidu, Hawaiian, and Portuguese), Diego Romero (Cochiti), and Pablita Velarde (1918-2006, Santa Clara). Previous exhibitions like About Face: Self-Portraits by Native American, First Nations, and Inuit Artists and Native American Modern have highlighted their respective work along with contemporaries like Helen Hardin (1943-1984, Santa Clara), Tony Abeyta (Diné), and Darren Vigil Gray (Jicarilla Apache). Works in the collection range from abstract to representational, exploring themes emerging from lived experiences, relationships to place, activism, and Native identities.

The Wheelwright Museum’s wide-ranging exhibitions have included groups shows of Indigenous artists across the Americas, yet the permanent collection primarily includes work by visual artists who have made their home in the Southwest or those associated with the Institute of American Indian Art. Previous shows have been responsive to different artistic movements in Native American art and American art more broadly, tracing emerging styles and techniques; examples include thematic shows like The Object is Graphic (1981), which focused on prints and posters (lithographs, serigraphs, etchings, and woodcuts). In the mid 1970s, the Wheelwright Museum launched the Indian Artist Series of shows that celebrated primarily sculptors and painters including Fritz Scholder (Luiseño) and T. C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo). Since this time substantial including one-person exhibitions at the museum have featured Tony Abeyta (Navajo), Arthur Amiotte (Lakota), Clifford Beck (1946-1995, Navajo), Shonto Begay (Diné), David Bradley (Minnesota Chippewa), Harry Fonseca (1946-2006, Nisenan Maidu/Native Hawaiian), Darren Vigil Gray (Jicarilla Apache/Kiowa Apache), Benjamin Harjo Jr. (1945-2023, Absentee Shawnee/Seminole), Allan Houser (1914-1994, Chiricahua Apache), Bob Haozous (Chiricahua Apache/Navajo), Judith Lowry (Pit River/Mountain Maidu), Pablita Velarde (1918-2006, Santa Clara Pueblo), and Emmi Whitehorse (Navajo).

Access is by appointment only, and all inquiries should be made emailing: collections@wheelwright.org.

Emmi Whitehorse (Diné)

Witch Seed I, #1147, 1997

Donated by the Estate of Daniel E. Prall

Photograph by Addison Doty

Linda Lomahaftewa (Hopi/Choctaw)

Evening Parrot & New Moon, 1983

Donated by the Estate of Daniel E. Prall

Photograph by Addison Doty

Michael Kabotie (1942–2009, Hopi)

The World in Chaos, 1964

Donated by Byron Harvey

Photograph by Addison Doty

Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (1940-2025, enrolled citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation)

Untitled, 1968

Donated by Susan Brown McGreevy

Photograph by Addison Doty

T.C. Cannon (1946–1978, Kiowa/Caddo)

Hopi with Manta, 1977

Purchased through the Daniel E. Prall Fund

Photograph by Addison Doty

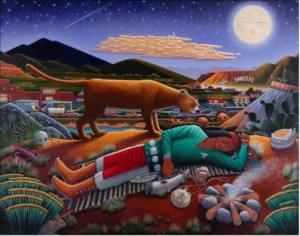

David Bradley (Chippewa)

To Sleep Perchance to Dream, 2005

Funds provided by Richard E. Nelson

Photograph by Addison Doty

Pueblo & Diné Ceramics

The pottery collection at the Wheelwright Museum consists of more than seven hundred works. The collection’s focus is contemporary Pueblo and Diné (Navajo) ceramics from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, tracing waves of historical change as well as distinct artistic lineages from across the Southwest.

The collection contains many visually striking works made using diverse techniques and materials, with a strong representation of Hopi and Pueblo artists from Kewa (Santo Domingo), Acoma, Cochiti, Nambe, and Santa Clara Pueblos. The Wheelwright Museum has a large collection of Cochiti figurative pottery, many of which are made by the Ortiz family, Damacia Cordero (1905-1989, Cochiti Pueblo), and Helen Cordero (1915-1994, Cochiti Pueblo). These were celebrated in the landmark exhibition Clay People of 1998. In addition, there is a selection of significant works by renowned artists Lonnie Vigil (Nambé Pueblo), Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo), and Marie Z. Chino (1907-1982, Acoma Pueblo).

There are more than two hundred Navajo (Diné) ceramics in the collection, which range from historic to contemporary. Some of the artists represented in the collection are Silas Claw (d.2002), Faye Tso (1933-2004), Myra Tso Kay, Alice Williams Cling, and Louise Rose Goodman.

Pottery remains important to Indigenous lifeways throughout the Southwest, used for various purposes such as storage and food preparation. When visitors began traveling on trains in the late eighteenth century, a new market for collectible pottery emerged. Indigenous potters from the Southwest creatively responded to this demand by making portable miniatures of pots and figurines for the market. Contemporary miniatures make up a significant portion of the Wheelwright Museum’s collection, reflecting this change in taste and style.

Knowledge of the materials and production of pottery is often passed to younger generations by family members. These intergenerational links are illustrated in the collection, which features works made by different members of the Duwyenie (Hopi), Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo), and Nampeyo (Hopi) families. The Wheelwright Museum works closely with living artists and descendant communities, demonstrating a commitment to foregrounding their voices through collections care and exhibition programming.

Access is by appointment only, and all inquiries should be made by emailing: collections@wheelwright.org.

Robert Patricio (Acoma Pueblo)

Polychrome jar with interconnecting diagonal butterflies, 2024

Provenance: donors through King Galleries in Santa Fe

Gift of Mary Roberts

Lonnie Vigil (Nambé Oweenge Pueblo)

Jar of micaceous clay, ca. 1995

Gift of Dan Prall Estate

Photographed by Addison Doty

Dextra Quotskuyva (1928 – 2019, Hopi)

Bowl with a scroll design in black and reddish brown on buff background, ca. 1967 – 1971

Gift of Byron Harvey III

Maria Martinez (1887-1980, San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Polished black pot, ca. 1966

Gift of R.B Jones

Faye Tso (1933-2004, Diné)

Pine pitched and inscribed jar with Yei’i figure, ca. 1985

Purchased with the Helen Gabriel Fund

Lucy Lewis (1890-1992, Acoma Pueblo)

White clay pot with fine line design, ca. 1956

Gift of R.B. Jones

Restricted and culturally sensitive items

The Wheelwright Museum stewards the founding collections linked to Hastiin Klah (1867-1937), esteemed Diné ceremonial practitioner, weaver, and co-founder of the museum. Klah’s access to Diné ceremonial knowledge was prodigious, and his legacy, stewarded by the Wheelwright Museum in dialogue with Navajo Nation, is direct and unique: it includes thousands of sound recordings (chants), 17 sandpainting weavings, and a range of personal belongings. Many of these items contain ceremonial knowledge and imagery, and as a result, they are considered culturally sensitive by Navajo Nation.

Beginning in 2024, we renewed our discussions with Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department (NNHHPD) regarding the stewardship of this important founding collection of Diné ceremonial art and intangible knowledge linked to Klah. This initiative reaffirms the driving intentions of our co-founders in developing a model of collaborative, sustainable, and ethical preservation practices to support access for Diné communities, now and into the future. Ethical stewardship means sustained dialogue with ceremonial practitioners and members of tribal government as well as family members, Native artists and museum professionals. Working in partnership with NNHHPD and other Diné stakeholders, our objective is to ensure the preservation of our founding collection and access for future generations. This is in keeping with our commitment to honor Native voices and Native expressions.

To build knowledge around this vital part of the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection, we are prioritizing the shared stewardship of Diné ceremonial belongings and recognize the responsibilities that this requires. We have formulated a plan to provide long-term support for the ongoing preservation, storage, and care of the Klah collections. The focus of our current collaborative work are Klah’s weavings, and we have been fortunate in 2025 to secure funding from the CORA Foundation and The Denver Foundation to help with these priorities.

All researchers and community members seeking access to these restricted collections are asked to obtain permission in writing from the Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department (NNHHPD), based in Window Rock, Arizona. These items can only be viewed by appointment once permission has been obtained from Navajo Nation, and with 4 weeks prior notice. Please note that we are unable to facilitate access to the collections or archives without an appointment. We request 4 weeks advance notice.

Access is by appointment only, and all inquiries should be made emailing: collections@wheelwright.org.

Textiles

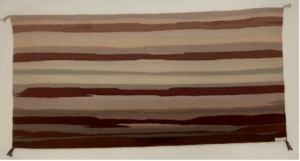

DY Begay (b. 1953, Diné)

Beyond Terrain, 2004

Donated from the Collection of Jack and Mary Purdy

Photograph by Ben Calabaza (Kewa)

DY Begay (Diné) is a fifth-generation fiber artist, internationally recognized for her abstract and painterly tapestries, many of which evoke Southwestern landscapes. Her work, Beyond Terrain, was featured in the artist’s first major retrospective, Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in 2024-2025. In creating her tapestries, Begay skillfully utilizes natural dyes made from plants that are sourced from her Diné homelands as well as her extensive international travels. Here, she has woven banded striations of deep red and beige, reminiscent of the New Mexico landscape, with water elements near the bottom border to represent Cochiti Lake. It serves as an important example of the contemporary weavings in the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection, which includes over five hundred textiles and wearing garments from the Southwest. Predominantly comprised of Diné and Pueblo textiles, the collection features exquisitely embroidered and woven items, such as mantas, dresses, sash belts, wearing blankets, serapes, pictorials, and other clothing items. Together, they represent the diversity of textile traditions and practices in the region, highlighting the transformations and innovations that have occurred over time.

Textiles hold economic, cultural, and spiritual value for Native communities, embodying Indigenous knowledge systems and lifeways. Historic and contemporary textiles show the influence of new materials and techniques, as well as the impact of intertribal trade networks, commercial markets, and evolving tastes in the region. Incorporating a wide range of patterns and design elements, from abstracted to pictorial, they also materialize community histories, personal stories, and lived experiences.

Previous Wheelwright Museum exhibitions, such as Nizhoni Shima’ Master Weavers of the Toadlena/Two Grey Hills Region (2010) and Centers of Influence (1977), have traced the emergence and development of regional styles throughout the Southwest while exploring the influence of traders, environmental and social changes, and multicultural textile traditions in the region. In recent decades, exhibitions have shifted focus away from collecting practices and regional trade networks towards Native cultural histories and aesthetics. Landmark solo exhibitions have further highlighted the work of living artists like Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi), whose masterful weavings bridge her unique vision with Hopi cultural references, and Morris Musket (Diné), an innovative and self-taught sash belt weaver and jeweler, as well as DY Begay.

Collaboration and consultation with Native communities remain core priorities in both collections care and exhibition programming, guiding methodologies for the culturally appropriate stewardship of textiles and all works in the permanent collection.

Ramona Sakiestewa (b. 1948, Hopi)

Basket Dance/9-B, 1992

Museum Purchase

Maker not yet known (Diné)

Banded blanket/Chinle Revival, ca. late 1800s-early 1900s

Cozy McSparron Collection, Chinle, Arizona and Fred Harvey Company

Purchased with funds donated by the Collectors’ Circle

Photograph by Addison Doty

Maker not yet known (Diné)

Serape, ca. 1840-1850

Gift of Olivia Rolte Johnson in memory of Harry R. Johnson

Photograph by Addison Doty

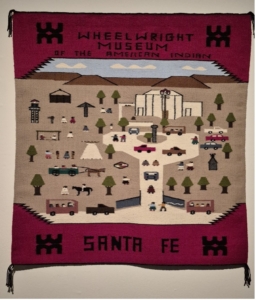

Ella Mae Begay (1958–2021, Diné)

Pictorial weaving, 1993

Donated by Susan Brown McGree